Description

A SIXTIES TRIP IN EVERY SENSE OF THE WORD…

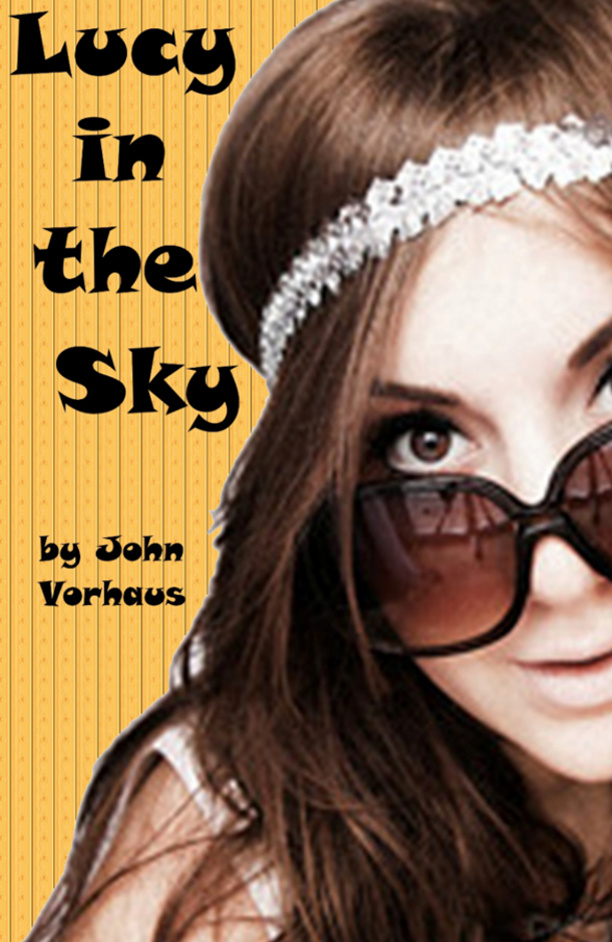

A coming-of-age tale set in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1969, Lucy in the Sky lightly touches on such weighty issues as the meaning of life, the purpose of art and the existence of God. For those interested in answers to The Big Questions or just keen to revisit a simpler time, Lucy in the Sky promises a fun and compelling trip – and that’s trip in every sense of the word.

Gene Steen is an earnest, intelligent, truth-seeking teen stuck in the cultural wasteland of his suburban home. He wants to be a hippie in the worst way, but hippies are scarce on the ground in the forlorn Midwest of Gene’s 15th year. Then, propitiously on the Summer Solstice, his life is turned upside down by the arrival of his lively, lovely, long-lost cousin Lucy. She’s hip beyond Gene’s wildest dreams and immediately takes him under her wing. Lucy teaches Gene that being a hippie isn’t about love beads and peace signs, but about the choices you make and the stands you take. Yet for all her airy insights into religion, philosophy and “the isness of it all,” Lucy harbors dark secrets – secrets that will soon put her on the run, with Gene by her side.

Lucy in the Sky resonates of such classics as Summer of ’42 and and invites the reader into a richly detailed vision of the ‘60s, as realized by Vorhaus’s sure-handed prose and authentic sense of place and time. With frank talk about sex and drugs, Vorhaus pulls no punches about the realities of the era, yet delivers an uplifting message about personal power and the path to enlightenment.

CHAPTER ONE: OIL AND STERNO MORE LIKE

This story is about the summer my cousin Lucy came to visit, and since she’s the star of the show you should hear how she sounds.

“The space program, Gene? The space program? They’ve got a lot of nerve calling this dinky neighborhood we live in space. Say they do put a man on the moon, so what? That’s just one flyspeck next to another flyspeck, you know? You can’t touch the infinite with rockets. You gotta go inside your mind, Gene, all the way down to your soul. Look at it. Live it. You’ll find out. It’s big as everything. Now there’s your space program.”

And she looks…amazing. Copper is her favorite color. She has copper hair, copper hairpins, copper earrings, bracelets, finger rings, thumb rings, toe rings, copper, copper, copper. Go Lucy, go with your copper. Go with your peasant skirts which wherever you got them it sure wasn’t Sears. Go with your chunky heels and funky sandals. Go with your lace leggings, oh my God. Go with your ankh necklace, and the other one, the leaded red cut crystal octagon that gives me Lucy times eight when I look through it, her halter top times eight when I look through it, no bra times eight when I look through it, oh God, Lucy, you cripple me, you slay me, you do.

She tilts down her copper sunglasses and I feel her eyes burning into me. I know she’s reading my mind. She knows I lust for her bust. My cousin! But if I know Lucy, she’d just say something like, “They’re only secondary sex characteristics, Gene. If it gives you pleasure to look, look.” ‘Cause that’s how she talks. She doesn’t talk, she blurts. Blurts!

She and my dad, though, cats and dogs.

Oil and Sterno, more like.

You know how you know when you’re always right? Me neither, but my dad does, and Lucy does, too, but they can’t both be right, that’d be like matter touching anti-matter and blooey! So blooey it is on Nixon and Vietnam, and blooey on civil rights. Blooey on short skirts and long hair. Blooey on pot versus booze. Blooey on Andy Williams versus the Who. Blooey on whether she should call him Uncle Carl or just Carl because Lucy finds honorifics ageist and classist, whatever those words mean. Blooey even on football versus baseball (barbaric versus boring and I say they’re both wrong). Blooey on everything because if she says black he says white, and that’s how the two of them are now. She’s under his skin. It’s really interesting to watch.

She’s under my skin. Been there since day one. Summer Solstice. Longest day of the year.

CHAPTER TWO: GROOVY DISCOUNTS

I’m horsing around in my treehouse with Gilbert, who’s not as dorky as his name sounds, in fact he’s pretty cool. He kypes his brother Wade’s Playboys and Rolling Stones and brings them to the treehouse. He likes the cartoons in Playboy, like this one of a Girl Scout showing her cones and saying, “Well, if you don’t want any cookies, how about a nice set of cupcakes?” I like the music reviews in the Stone. Neil Young played last week at the Troubadour on the Sunset Strip. Man, what I wouldn’t give to be on the Sunset Strip. Or even anywhere, because everybody knows this is nowhere, this treehouse in Milwaukee or even anywhere in Milwaukee. And also nowhen because while it might be the 1960s where Mr. Neil Young lives, it sure as fudge isn’t here, not while I’m still getting my hair cut by Luigi the homuncular barber, and my clothes come from, yep, Sears, and a big night out for the Steen clan is eating at the Jolly Pop Drive-In and seeing Those Daring Young Men in Their Jaunty Jalopies.

(And not while I’m still saying fudge instead of fuck. You know?)

So it’s Saturday, June 21, 1969, here at the corner of nowhere and nowhen, the first day of summer and the first day of summer vacation and less than a week until I turn fifteen. “Hair” by the Cowsills is playing on WOKY, the Mighty 92, on the bulky brown transistor radio I keep up here in the treehouse. Being almost fifteen, I’m almost too old for a treehouse, but I’m kind of calling it a clubhouse now, or even a redoubt, which is a word I learned for hideout or lair. I know words. I like learning them. Plus geography, geology, biology, psychology. I’ve always been a pretty good student, not because I’m trying to earn Brownie points, but just because I dig it. Though more and more these days I can’t help feeling like I’m learning the wrong stuff, the stuff that doesn’t matter. Where’s the stuff that does?

So lair. I’m in my lair. Listening to “Hair,” “Hair” in my lair. But keeping the volume down though, because Dad’s down there mowing the lawn and Dad doesn’t like rock and roll, though how the Cowsills are rock and roll I don’t know. I mean, they’re not exactly radical, are they? They even wear the same clothes, and in my opinion, no one can really be rock and roll if they wear the same clothes, not since the Beatles cut it out. But this nicety is lost on my dad. If it isn’t anciently old, it isn’t music to his ears. And it’s nonsense, what he listens to. I mean, granted, “Hey Jude don’t make it bad” is hardly Walt Whitman or even e.e. cummings, but on the other hand, “Flat foot floogie with a floy floy?” What the hell’s a floy floy?

Rolling Stone has a thing on when Jim Morrison flashed his wiener at this concert in Miami last winter. I would like to’ve been there. Not that I’d want to see the Lizard King’s wiener, but still.

It’s already hot, summer hot, but not humid like it’ll get. Come August I’ll be totally broasting, sleeping naked in my bedroom in the ovenlike upstairs of our house, with the windows open and the sheets thrown back and the ceiling fan squeaking loudly on its cruddy ball bearings and me wishing it would at least have the decency to suck up a mosquito or two. Now, though, it’s still okay. Hot for sure, but not oppressive, and the maple and oak trees up and down both sides of the street make pools of cool shade on the concrete slab sidewalks and the lush green lawns that front all the cream colored brick two-story homes.

My lair looks almost straight down on the street. If you wanted, you could chunk water balloons on the roofs of passing cars. Or heave ones at Dad as he mows, an act of D’Artagnian rebellion that would never in a million years have crossed my mind during these last five minutes of my life before Lucy arrives. Right now I’m let’s face it quite a square, a rebel without a clue. I don’t smoke dope or even coffin nails, or curse or shoplift, and I even still enjoy Those Daring Young Men in Their Jaunty Jalopies, though I know it’s not cool to admit it. I’m not cool, I admit it. I even have a very not cool name. Gene. Eugene Montgomery Steen.

I mean, come on.

But there’s a streak in me. Iconoclast, I guess you’d call it, or maybe just weirdo. Anyway, I like to do dumb things if I get the chance. Like, here was my school science project from last year: “How Stupid Are Science Projects?” It was a joke, because actually I like science, but serious too, because I did it like you’re supposed to, all scientific method and such. I took a survey, correlated the results and reported my conclusions, supported by pie charts, bar graphs and good ol’ Venn diagrams. I even had control questions like, “How stupid is Gomer Pyle?” (A hundred percent stupid, hence the control.) Sixteen percent of adults surveyed thought science projects were stupid. Ninety-three percent of kids did. I should have called it, “How Stupid Are Adults?” but anyway.

So I’m up in the air in my lair when I notice this VW microbus coming down the street. “Hey, Gilbert,” I say, “check it out. Hippie van at six o’clock.” I don’t know if six o’clock is actually the direction I’m looking, but I know from the TV show Twelve O’Clock High that twelve o’clock high is straight ahead and up, so I know it can’t be that. Maybe it’s six o’clock. Maybe it’s 7:23. Anyway, here comes this big beater of a van with a bumblebee black and yellow yin yang painted on the front, and trust me, hippie vans don’t roll down streets like mine every day, or even any day ever. So this is news.

Gilbert slides over and we peer down through the redoubt’s redwood rails at the microbus, which is riding low on bald tires and belching sooty uncombusted gas, and just couldn’t look more out of place in this neighborhood of Dodge Darts and Oldsmobile Vista Cruisers. But it catches my eye because it looks hippie and anything that looks hippie catches my eye these days, even the ads in the Milwaukee Sentinel which have lately started sticking flowers and peace signs into the graphics and offering “groovy discounts” on dinette sets. I know it’s bogus, but there’s not a lot I can do about it. I’m like a moth to a flame with hippie stuff because this is Milwaukee and when I tell you that flowers and peace signs in newspaper ads are about as hip as this place gets, I’m not exaggerating all that much. But I’m so hungry for it, man. I mean, imagine you’re a caveman eating raw mastodon and you hear that some other guys somewhere have been farting around with something called fire. You don’t know what fire is, but you hear it does awesome things to meat. You’d naturally want to try it. You’d crave to. That’s the way I feel. I’m a caveman living in a cultural cave and I’m getting sick to death of eating raw mastodon, which, yuck.

Then the van does something I’d never expect it to do, not in a million lifetimes. It stops right in front of my house. No vans like this ever stop in front of houses like mine. It might as well be a spaceship.

Well, in a sense you could say it is. It surely contains an alien.

CHAPTER THREE: MARYJANE VIRGIN

The van knocks and pings as the driver driving it shuts it off. This draws Dad’s attention. He looks over at the microbus, but keeps pushing the push-mower because he’s a dog with a bone with that lawn, it’s his joy and pride. Last year when Milwaukee was considering banning phosphate in fertilizers, Dad stocked up. On that and DDT, too, which he filled a whole back room of his hardware store with, because he feels about bugs like he feels about crabgrass: Enemy! Die! Now he’s got enough banned pesticides to keep his lawn going through Armageddon, and that makes him happy.

What doesn’t make him happy is hippie vans parked at his curb and though he’s still got the push-mower going whiska-whiska, he’s got an eye on the van, too, possibly sizing it up for a good dose of DDT just in case. Then the side door slides open, squeaking on rusty rollers, and a big, metal-frame backpack flies out and thuds on what they call the parkway, the strip of city grass between the sidewalk and curb (which Dad tends grudgingly because its city property and they should care for it but he’ll be, and I’m quoting here, “good Goddamned” if he’ll let any part of his cherished domain be an eyesore, you betcha).

The science project I didn’t do last year was “Does Heat Really Rise?” which my teacher, the dreaded Miss Buchanan, rejected because of course heat rises and she said I could do better than that if only I Applied Myself, which led to “How Stupid Are Science Projects?” which she even had to give me a good grade on because after all I did do the work. But heat does rise, this we know, and smells rise with it, which is why I smelled burning oil and the reek of brakes and cooked anti-freeze coming off the van, and then when the door opened something else that the news magazines like to describe as “sickly sweet,” but I think is more like sage gone bad.

“Is that what I think it is?” asked Gilbert who, so far as I know, is a maryjane virgin like me, but we both spent enough time in the boys’ room in junior high to know the difference between cigarettes, which everybody smokes, and dope, which only the Afro-Americans and the drama kids smoke. I shushed Gilbert and we crouched down lower, because between the hippie van and the pot smell and the backpack flattening Dad’s precious Perennial Ryegrass (even if it was city property), I sensed that the situation could get edgy. Dad took a couple of steps toward the street, stopped, put his hands on his hips and just radiated disapproval. It’s easy to know when Dad’s angry, his shoulders scrunch. And he hates hippies like a cat hates baths.

I saw a foot first, then another, both wrapped in strappy sandals that crisscrossed the calves all the way up to the knees. Then came the hem of a calico sundress fluttering in the June breeze, and then the rest of her, all willowy arms, jangling bracelets, suede leather handbag and giganzo lavender floppy felt hat. In a voice kind of husky but also sort of lilty, she said, “Thanks for the lift, dudes,” and blew some kisses back into the van. She closed the door behind her and the van labored off. Then she took off her hat and shook out her gorgeous unstoppable copper colored hair, letting it fly free.

Can you fall in love with the top of a head? I kind of think you can.

Gilbert gawks. I gawk. Dad gawks, but not in a good way as it dawns on him that for some utterly inexplicable reason, this chick thinks that wherever she’s going, she’s there. He steps forward to disabuse her of that notion PDQ. “Can I help you?” he says, which doesn’t sound at all like can I help you except if he means can I help you go away?

“Uncle Carl?” she asks, but from the way she says it, almost a squeal, you know she doesn’t think it’s a question. She beams him a smile you can see from space.

“Yes, I’m Carl. Who are you?”

The girl acts surprised. “What do you mean who am I? I’m your niece, Lucy.”

At this point she kind of dances past him and pirouettes around on the lawn, just happy to be out of the cramped confines of the microbus, I guess. We already know how Dad feels about his lawn, so he’s not likely liking this very much, but he likes it a whole lot less when she dances back to him, throws her arms around him and gives him a big hug and a wet smooch on the cheek. He recoils like she’s wrapped hot snakes around his neck. He doesn’t like to be touched. “Where’s Aunt Betsy?” Dad mutters something I can’t hear, and the girl says, “Great! I can’t wait to meet her!”

She bends over to pick up her backpack. I can see right down her dress.

I swear I see a nipple.